Swiss Allotment Gardens: Where "Me Time" Meets "We Time" - a Realisation driven by the Understanding of the Megatrend Individualisation

- Bettina Eiben Künzli

- 22. März 2024

- 7 Min. Lesezeit

Aktualisiert: 23. März 2024

2023-03-21

Today's post is a labyrinth of complexity, requiring careful navigation of each twist and turn to bring clarity to the journey ahead. It feels as though I'm preparing for an exhilarating ride, with each step requiring meticulous attention. So, brace yourselves, dear readers, for what lies ahead promises to be quite the adventure. This is a creative thinking space and all is possible - or not.

From Squabbles to Systemic Shifts - Unveiling the Unexpected in Allotment Gardens, Discovering Mytopia

This expedition initially set sail with a simple objective: to resolve conflicts within allotment garden associations using the principles of design thinking. The mission was clear - understand these conflicts, identify areas for intervention, and devise solutions. However, it soon became apparent that a mere band-aid approach wouldn't suffice. A deeper exploration was warranted - one that not only resolved conflicts but empowered associations to navigate them adeptly, fostering resilient and sustainable commons for the future. As my research journey progressed, a captivating truth began to emerge - these conflicts were not isolated problems but rather threads woven into a much larger tapestry of societal change.

This revelation marked a turning point, as I realised that I had been viewing these conflicts through a skewed lens, coloured by my own perspective bias. It wasn't until a recent coaching session and reflective discussions with Nico, a cherished friend of just over a year, that the veil was lifted. With a deeper understanding of the megatrend of individualisation, I began to see things in a new light.

Here is the story:

Exploring the concept of individualisation shed light on the root causes of conflicts within allotment associations. What may have appeared as problems initially, I now recognise as part of a transformative societal process. I began to understand that my previous pessimistic view of these conflicts stemmed from a disruption of balance and fairness, impacting both human and non-human members of the community. But why? I guess it was a reflection of my deep-seated concern for the well-being of the community and its environment - a shared responsibility I held dear. This reflection did something to me. And I had to investigate what it was.

As I went deeper into dialogue with gardeners, board members and others, observation, and engagement, a profound shift in perspective unfolded. These conflicts were not isolated incidents but rather reflections of my mindset and worldview. My perception of the world, my areas of focus, and my interpretation of information all played a significant role in shaping the trajectory of my research. It was akin to discovering "Mytopia" - a network of interconnected personal perspectives that coloure(d) my understanding of the world.

Although at this point of my research, all seemed to get clearer, I still wondered, how the Megatrend intersects with my research, and how it has influenced my approach.

Co-Individualisation in Action: A Case Study within a Case Study

As I write this post, upon reflection I begin to realise something: Within the realm of allotment gardens, individualisation seems to manifest as co-individualisation - a fascinating concept where personal fulfilment coexists with a strong sense of community. This phenomenon is evident in the growing trend of gardeners forming commons within the garden community, whether through formal agreements with the association (usually two people sharing a garden) or informal arrangements among like-minded individuals (two or more people co-gardening, while one person is under contract). Currently, 7 out of 50 plots are examples of what I perceive as practised co-gardening communities. However, co-individualisation isn't without its challenges. One plot, for example, initially managed by eight people, highlights this complexity. The co-gardening group downsised to four over time due to clashes in values and differing understandings of co-creation, collaboration, and co-harvesting. This group experienced various internal conflicts – a microcosm of the challenges that can arise within a larger community. For instance, the roof association. Which in our case is the allotment garden association.

The Law of Cause and Effect: There is a Cause for every Effect as there is an Effect for every Cause

The specific issues, as conversations with various people revealed, stemmed plausibly from a combination of factors: individual personalities within the group, difficulties finding and maintaining common ground (especially with replaced community members), and potential contradictions between their co-gardening contract and the association's regulations. Notably, only two of the eight members were officially listed in the contract, which the allotment board saw as a violation of the overarching community agreement. Contact was made, but the tenant's response up to this day is far from cooperative and collaborative.

The Law of Correspondence: How the response (resonance) to "WHAT IS" effects "WHAT MIGHT BE"

This situation presents a fascinating viewpoint and highlights the difference between the polar and non-polar perceptions of things. What appears as a clear-cut conflict for the board, and a clash of interests for the plot community (who felt misunderstood and justified in their actions, perceiving the conflict as a violation of unrecorded agreements between the previous board and the new one), reveals something much bigger. The board perceives the situation as a problem reacting in its own comons sense (polar perception: battle mode) but does not identify it as a potential for learning and growth, wheras the plot community feels challenged in its rights und underastanding of community practices (victim mode). Both are unclear of the root cause, and both respond reactively to each others actions. Clearly, both stakeholder groups demonstrate a polar perception. (The following unfinished graph will explain the concept of polar and non-polar perception in its basics) .

This case study demonstrates the complexities of co-individualisation in real-life situations. While some groups may thrive under shared management, others may struggle. The key lies in the ability to mutually listen free of judgement, summarise and extract the received, redirect the incoming energy, and answer following the concept of open communication, showing a willingness to compromise, embracing the shared understanding of the co-gardening contract and association rules.

This situation underscores the importance of flexibility, response to environmental change, open communication and a willingness to compromise in navigating conflicts within allotment associations. Here, Hartmus Rosas book "Resonance" (2016) comes to mind. His concept will be explained in its basics in the following mind map:

(To access the high resolution PDF file, check the document below):

From my perspective, this includes for instance formalising roles and responsibilities within the co-gardening group through a well-defined contract or set of principles (in buiness context often refered to as team canvas) which usually helps to avoid misunderstandings. Further, I think, finding and maintaining common ground is inevitable. Matching individuals with similar gardening philosophies and work styles can enhance the success of co-gardening arrangements, while flexibility and adaptation are key in managing diversity and complexity. Hence, a culture can be intentionally formed and maintained by design, no matter, how tall or small the community. In practice this means that in an association with three different garden areas, three different forms of culture might arise. And in these shared spaces, sub-cultures need places to thrive.

Flexibility and adaptation could be a potential approach for allotment associations to manage diversity and complexity. As we are aware, co-creation is an ongoing process. By preparing to adapt to the emerging trend of co-gardening and neo-tribe-creation and upon reflection on the group's evolving needs and dynamics, the association board might foster a strong community bond. By acknowledging these challenges and fostering open communication, on the other hand. allotment garden associations might empower co-gardeners to navigate these complexities themselves. On consequence, by acknowledging these challenges and fostering open communication allotment associations might be able to create vibrant and resilient garden communities that celebrate both personal expression and a strong sense of belonging.

To me,, this newfound understanding opens up exciting possibilities. By reframing conflicts as opportunities for growth and community building, allotment garden associations can navigate change productively, transforming challenges into catalysts for positive transformation.

Practice vs. Theory

Observing gardening activities through a new lens, I have witnessed the power of collaboration in fostering a sense of community and purpose. Diverse groups are forming within allotment gardens, creating a vibrant tapestry of belonging. This is the essence of co-individualisation in action - a celebration of personal expression within a supportive community.

Belonging and Self-Expression

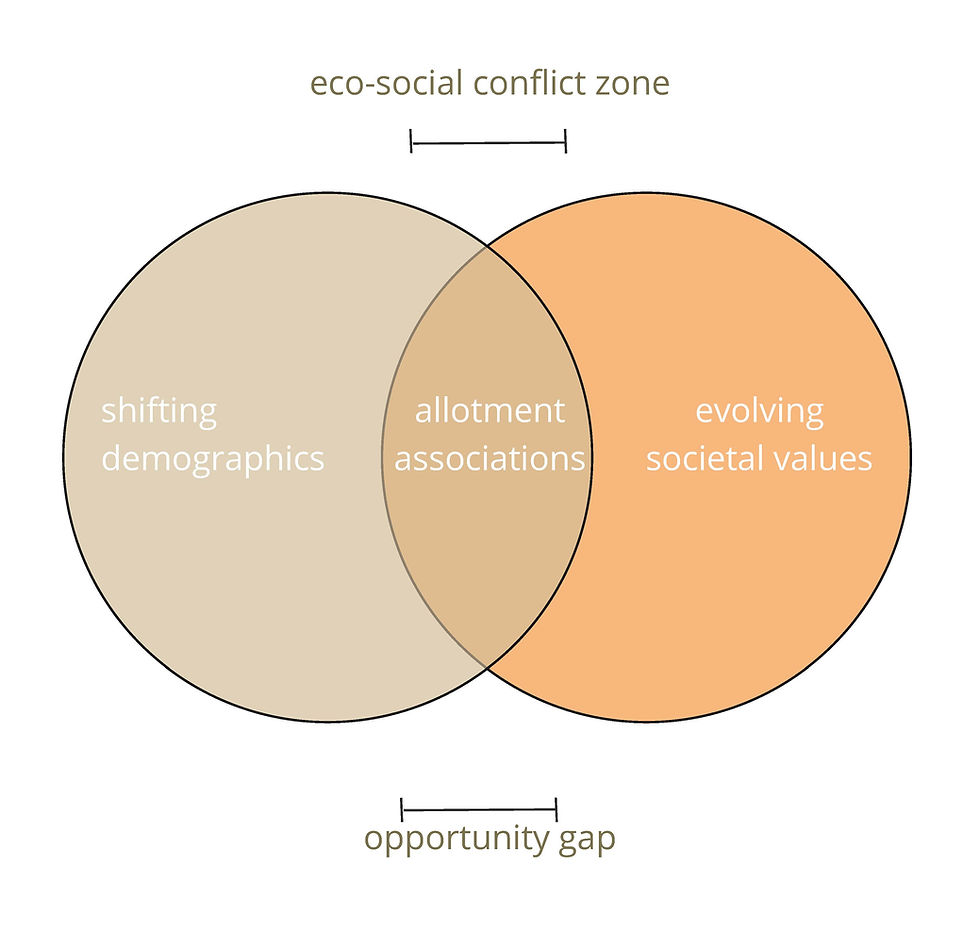

Already the learned offers a fresh perspective on resolving eco-social conflicts. I understand now, allotment gardens provide a space for self-expression while fostering connection and collaboration, offering a glimpse into a future where personal fulfilment and community thrive hand in hand.

Returning to the Macroverse

I'm left pondering. What if this observation means more? What if the transformative process unfolding in allotment gardens is a microcosm of something much bigger or the much bigger is reflected in this microcosm? Could the crises we see dominating headlines – climate change, social unrest, etc. – be misinterpreted by our economic mindsets? And if so, how does that translate into my case? Perhaps crises are not just isolated problems, but rather symptoms of a deeper transformation unfolding before us. Slowly I get by reframing these challenges as opportunities for positive change, we can unlock new pathways towards a more sustainable future.

A shifted Perspective

This possibility is both exciting and daunting. It suggests that our (the boards and my) current lens of crisis management might be limiting. By reframing these challenges as indicators of transformation, we might unlock new pathways for navigating change and fostering a more sustainable future. The allotment garden experiment, then, offers a valuable model for understanding and navigating large-scale societal shifts. Examining these microcosms of change might be the key to unlocking a more nuanced and optimistic approach to the challenges we face as a global community.

Perhaps the general struggle to see these crises as potential turning points is linked to an inflexibility in how we respond to incoming information. We often fall into the trap of binary thinking, categorising things as good or bad, threat or opportunity. This rigidity makes it difficult to grasp the complex and multifaceted nature of change. Are we truly aware of all the initiatives and organisations out there that are approaching these challenges with a more nuanced, non-polar perspective? Are we actively seeking out these examples and learning from them? By embracing non-polar responses and fostering a more open and adaptable mindset, we can better equip ourselves to navigate the complexities of a changing world. It's not about ignoring problems or pretending everything is rosy. It's about acknowledging the potential for positive transformation within challenges and seeking out those who are already approaching them with this perspective. The allotment garden might just be a small-scale example, but it offers a powerful lesson: sometimes, what we perceive as a problem can be the very thing driving positive change.

In conclusion, allotment gardenassociations offer not only a space for personal growth and expression but also a platform for fostering connections and sharing knowledge. By embracing the principles of co-individualisation, allotment garden associations can cultivate a culture of collaboration, sustainability, and community, paving the way for a brighter future.

Kommentare